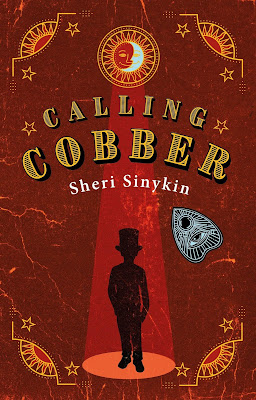

Review: Calling Cobber

Calling Cobber by Sheri Sinykin

Early on in Sheri Sinykin’s middle grade novel, Calling Cobber, 11-year-old Jacob “Cobber” Stern’s English teacher asks him to compose a haiku about himself and his family history. Cobber writes: Me? I am nothing./No culture, no heritage./I am just Cobber. He is a boy adrift, without an anchor to steady him in his uncertain world. Cobber doesn’t know how to communicate with his emotionally distant, workaholic father since his mother’s death six years ago. He’s not sure if his friendship with BFF Boolkie Berman can survive now that Boolkie has “abandoned” him for Hebrew School and bar mitzvah studies. And he feels increasingly responsible for his great-grandfather, his Papa-Ben, who still lives on his own but is becoming more and more forgetful. All of this uncertainty leaves Cobber feeling grief-stricken, fearful, and defeated. Underpinning Cobber’s troubles is his contentious relationship with his faith. Sinykin is unclear as to why Cobber rejects Judaism, especially considering how much being a Jew means to his beloved Papa-Ben. But events compel Cobber to work through these complicated emotions, and he eventually begins to understand the strength and connection that Judaism provides. Several incidents in Calling Cobber strain credulity. Is the reader supposed to believe that Cobber is actually communicating with his dead mother through a Ouija Board? Is it possible for Papa-Ben to take all of his prescription pills at once and survive? Would Cobber really be able to persuade his father to move Papa-Ben into their house so easily? Despite these head-scratchers, readers will root for Cobber as he faces profound questions about himself and works through his pain in ways that are both touching and relatable.

Calling Cobber is well-suited to its intended audience of 8-12-year-old readers. It’s a story of family and faith, not a book for those seeking thrills and adventure. Cobber’s relationship with Judaism is at the core of Calling Cobber. The book portrays religion in a generally positive light, despite Cobber’s negativity throughout much of the book. Judaism has tremendous meaning for Cobber’s Papa-Ben, and he tries to instill this in his great-grandson. But Cobber must decide on his own what Judaism means to him. Some Jewish parents may balk at how Cobber’s father shrugs his shoulders at Cobber’s determination not to have a bar mitzvah or go to Hebrew School. Such a decision may be nonnegotiable in a lot of Jewish households. Still, Cobber’s struggle will ring true for readers dealing with parents who approach religion in very different ways. Sinykin infuses Calling Cobbler with Jewish sensibilities and concepts, and its sensitive portrayal of a Jewish boy coming to understand what his religion could mean to him make it a viable contender for Sydney Taylor Notable Book status.

Are you interested in reviewing books for The Sydney Taylor Shmooze? Click here!

Comments

Post a Comment